You are here

D’s and F’s: Irving ISD’s dismal scores on statewide report draw gasps, vows of change

By Avi Selk

Last month, I skipped a weekend fundraiser for Irving’s cash-strapped after-school program.

“What could go wrong?” I thought.

Shows me. I spent the next week conducting a mini Warren Commission investigation on the event, after a parent convinced a school board member that it was actually a political rally. (Conclusion: it wasn’t.)

So I made sure not to miss last Friday’s community luncheon with the head of an education nonprofit. Even before it took place, rumors were swirling that the speaker—Children at Risk President Bob Sanborn—might launch a public attack on the school district.

With the fundraiser fresh in my mind, I wanted to witness the luncheon myself, lest I spend July swatting down reports that it was actually a Weathermen rally, or something.

It wasn’t, of course. But it was an interesting couple of hours, full of blunt speech, bleak statistics and a bit of indignation from the audience. In a cafeteria-sized room at Bear Creek Community Church, Sanborn told about 50 parents, residents and even a couple City Council members how his organization came to rank Irving ISD the worst large school district in North Texas.

“As residents of the community, we are not trying to sell the community to outsiders,” Sanborn said. “We’re trying raise our kids, we’re trying to send them to high-quality schools, and we’re trying to make sure every single kid has the opportunity to be successful.”

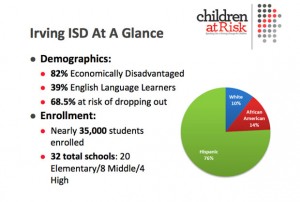

And with that, Sanborn launched into a slideshow illustrating the difficulty of doing those things in Irving ISD. I wasn’t shocked to see the huge numbers of students whom the state has deemed at risk of dropping out (right). I was familiar with these stats, which are similar to those in most other inner-ring suburbs of Dallas.

From the gasps I heard in the audience, I think I was an exception.

The numbers got worse. Children at Risk doesn’t simply parrot the Texas Education Agency’s official state ratings, which are often criticized by education experts as being too lax. (As Sanborn put it: “The goal of the TEA is to look good.”)

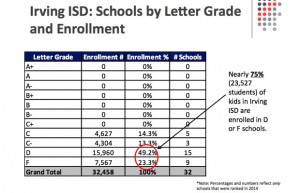

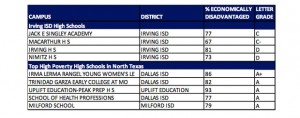

When Children at Risk grades a school from A to F, it considers whether students’ test scores are better or worse than other schools with comparable populations. The nonprofit also considers whether students are improving year after year, no matter how low or high their test scores are to begin with. The idea is to level the playing field between, say, MacArthur High and Highland Park High, so that even high-poverty districts like Irving can get A’s if they are doing the best job possible with their respective populations.

But MacArthur did not get an A. In fact, no school in Irving ISD got anywhere close to any A.

Said Sanborn: “If you’re a researcher with no reason to look at ISD, but you look, what you’d say is: ‘I’m very surprised there are no A schools. I’m very surprised there are no B schools.’ There are many, many school districts with high poverty that have B schools but there’s none in Irving ISD. There aren’t even any C-plus schools.”

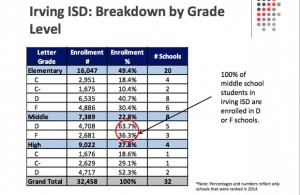

Three quarters of Irving ISD students, and every single middle schooler, attend D or F schools, Sanborn said.

More murmurs from the audience.

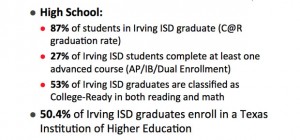

Sanborn pointed out a few bright spots in Irving ISD, which beats the state’s average graduation rate and college readiness rate.

And he talked about how the district could do better. To prove it was possible, he cited A and B schools across Texas with even poorer populations than Irving’s.

He specifically highlighted Alief ISD near Houston. It’s bigger than Irving and has the same level of poverty, but it score a B average compared to Irving’s D.

Children at Risk pays special attention to high-poverty schools that score well on its reports. It’s found some commonalities between them, Sanborn said: “a missionary zeal in teachers,” more classroom time for students, administrators who study their and put it to use, and high-quality Pre-K and after-school programs.

Irving ISD’s scores aren’t uniquely bad. Sanborn spent as much time talking about the district as he did about Texas, whose education system lags most other states.

“We live in a world where 60 percent of our children will need some kind of advanced education,” Sanborn said. “But only 22 percent of our kids are going there.”

Sanborn’s audience ran the gamut from high-school parents and community activists to Irving ISD attorney Berth Whatley (who announced that she was there in her individual capacity.)

Council member Dennis Webb was there, which isn’t surprising since he hosted it at his church. So was council member Oscar Ward, who stood up after Sanborn’s presentation, took his “councilman’s hat off” and said he was so impressed with the report that he wanted to share it with the school board.

“Why don’t you and me take it to them?” Webb suggested, to applause.

No one from the school board was in the audience. Some may have been tied up in training, but their absence was noted.

“The superintendent is not here. No one from his inner office is here. The school board isn’t here,” said Maurice Walker, Irving ISD’s parent involvement coordinator. “That speaks volumes in my mind about what they think about our children at risk.”

“I’m sure the school board cares a lot,” Sanborn said. “But they need to understand every issue.”

The audience Q-and-A morphed into a series of speeches about how people far removed from the school district’s top ranks could hope to reform it.

Jim Deatherage, who worked for decades as Irving ISD’s attorney before he fell out of favor with the school board, rose to speak.

“I understand economic disadvantage,” he said. “I’m the son of a poor Pentecostal Ozark preacher. Usually, Sunday meal was maybe if somebody brought us a chicken.”

“I’m not economically impoverished today, so it’s no excuse,” Deatherage said, louder. “The only way Irving is going to get its students and its schools above the median line–we ought to at least be in the upper half, not down in the lower half, not down in the lower third, sometimes the lower 10 percent–[is to] use this report of Children at Risk and their assistance as a catalyst to interest other people.

“And it’s going to take a lot of meetings and it’s going to take a lot of work.”

Webb looked set to kick the meetings off when he offered to share the report with not just the school board, but also with other city council members.

“I was somewhat surprised when I saw the info that was sent to me about Irving’s ranking,” Webb said. “I was kind of in deja vu land, thinking everything was perfect in the Irving school district until I got that information.

“One of the keys of where we go from here is we don’t be afraid to let people know we’ve got some issues.”

Bob Sanborn’s slideshow on Irving ISD is reprinted below.